My latest (in VQR, Virginia Quarterly Review), and most personal ever, on my dad, my family, and the new science of narcissism. Link is HERE

OUT NOW!

“The Mind of the Artist”

Order HERE.

JACKET COPY:

Because artists make something out of nothing, the process can seem like magic, divinely inspired and inexplicable. It’s not. A single, potent factor lies at the heart of most everything creative: the mysterious, multi-faceted trait of “openness.” This book describes the role of the openness dimension in the typical artist mind: how it loosens thinking, how it widens feelings, how it motivates behavior, how it stimulates an inner chaos encouraging artistic invention. For creatives, openness is a unifying glue. It binds together states and processes at the core of the art making impulse. A related key variable is trauma, according to scientific findings: the raw material with which so many artists work. In novels, poems, stories, and photographs, trauma gets symbolically repeated, shaped in the direction of a torturous beauty. Scientifically astute, conceptually subtle, and packed with richly-detailed artist examples—from David Bowie to Frida Kahlo, from John Coltrane to Francesca Woodman, from Diane Arbus to Kurt Cobain—The Mind of the Artist demystifies artistic genius. It is a new, true portrait of artistic vision.

ADVANCE PRAISE:

A brilliant psychologist takes on the question of what makes artists artists. And yes, he has data. And rigorous research. And superb intuition too. (Did I mention style?) One of civilization’s great mysteries — solved! Or closer to solved. What an adventure!

–Walter Kirn, New York Times bestselling author of Up in the Air, Thumbsucker and Blood Will Out

This book blew my mind. It grabs you right away and you can’t put it down. Fascinating and brilliant, beautifully written. It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen on the subject before. All artists should read it.

–Asia Argento, actress, director, writer, artist

There is no way to be more rigorous and comprehensive in one’s research or more thrilling and illuminating in presentation. The great mystery of creativity bursts into clarity in these pyrotechnic pages. This book will make you rethink everything you know about art, psychology, yourself — a critical step in cultivating an artist’s outlook.

–Yelena Akhtiorskaya, author of Panic in a Suitcase

A book on artistic creativity should be written by a creative author – and Todd Schultz has one of the most creative minds in psychology today. Drawing upon personality science, personal experience, and a wealth of biographical vignettes, Schultz presents a fascinating and truly unique perspective on what it means to be an artist and how artists do their creative work. There are insights here for artists themselves, as well as psychologists, and for so many of the rest of us who aspire to be more creative in our thinking, in our work, and in our lives.

–Dan P. McAdams, The Henry Wade Rogers Professor of Psychology, Northwestern University, Author of The Strange Case of Donald J. Trump: A Psychological Reckoning

Creativity often gets discussed in airy and imprecise ways, but the science behind it is unassailable. In this extraordinary, elegantly written book, Schultz shows us the psychological research, tracing it through the lives of various artists—John Lennon, David Bowie, Sylvia Plath, Frida Kahlo—to elucidate how personality lays the foundation for the states of mind in which art gets made. Essential reading for artists and anyone curious about the creative process. In other words, for pretty much everyone.

–Amanda Fortini, Beverly Rogers Fellow at The Black Mountain Institute and author of the forthcoming book of essays, Flamingo Road

Books about creativity and ‘unleashing your inner artist’ are a dime a dozen. With The Mind of the Artist, we have something entirely different – a serious, nuanced, evidence-based look into the research behind creativity and what separates Picasso from the hobbyist down the street.

–David J. Morris, author of The Evil Hours: A Biography of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

William Todd Schultz has x-ray vision for the creative psyche.

–Joshua Wolf Shenk, author of Powers of Two: Finding the Essence of Innovation in Creative Pairs

No reaction, no disorder

New blog post on the DSM 1’s surprisingly sharp take on anxiety and why, to make anxiety go away, you have to stop trying to make anxiety go away! HERE

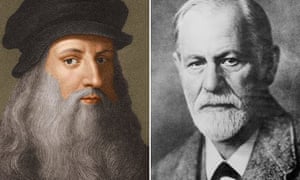

Art: 1, Freud: 0

Fresh blog post on the one thing Freud admitted he could never explain. LINK

Papers in Psychobiography

I thought I’d post links to some old work here, stuff that may be hard to find. I can’t say I love these pieces equally. In fact, a few are (to me) almost cringeworthy, but then you keep growing and keep getting better and better. Every new project almost invalidates the old! Not totally of course. Or maybe not at all. Anyway, here are a set of old pieces. I may add more over time.

- My very first academic publication. What I was interested in here was the connection between early loss and creativity, especially in writers. Subjects are James Agee and Jack Kerouac: an orpheus complex in Agee and Kerouac

- When my kids were little they went through a serious “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” phase. For several weeks we watched the film almost every day. Slowly an interpretation dawned on me and after looking into it, I decided to write it up. Loss figures in this essay too, so in some ways it’s a continuation of the article above. finding fate’s father Roald Dahl and loss and Wonka

- I wrote this in a shed in my backyard. The subject is Ludwig Wittgenstein’s fear of death/suicide and its effect on his philosophizing. Wittgenstein and death fear

- This one is pretty bad but parts still seem valid and/or interesting. It’s a floridly Freudian interpretation of James Agee’s masterpiece “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” James Agee Let us now praise famous men

- I wrote this during a time I was very involved in Buddhism and thinking about things like satori and much more. It’s on Oscar Wilde’s prison experience and the psychology of epiphany. Prison as a turning point Oscar Wilde

- I like this piece. It’s dark and dense and feisty. I wrote it in an isolated cabin on the Oregon coast and the setting fit the theme: Sylvia Plath and her attempts to hate her parents into valuelessness. mourning melancholia & Sylvia Plath

- A methodological chapter I also like a lot on how to strike psychological paydirt in biographical data. In two parts: striking paydirt in biographical data 1 striking paydirt in biographical data 2

- This is short, also sort of methodological, and lots newer. The person I talk about most here is Bowie. behind the masks

- About Peaches Geldof. This is a remembrance rather than a psychobiography. Peaches talks about the trauma of fame. I adored her and miss her. Peaches and me

- Now, stuff that is newer (relatively). A book chapter on the Psychobiography of Genius in which I discuss one genius (Capote) and one non-genius (George W. Bush), and a review article from American Psychologist on Psychobiography Theory and Method. Psychobiography of Genius Psychobiography Theory and Method

- A never published essay on Jack Kerouac and how the loss of his brother Gerard prefigured so much of his fiction and fueled his need to write, with the un-shy title “The Whole Reason Jack Kerouac Ever Wrote At All” Kerouac Psychobiography

- From my book on Truman Capote, chapter one. The book is Tiny Terror: Why Truman Capote (Almost) Wrote Answered Prayers. Chapter here > Tiny Terror Capote Chapter One

- Then finally (for now), here is the first chapter from my book on photographer Diane Arbus (An Emergency in Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus). diane arbus essential mysteries

Flashbulb Songs #1: The Floyd and the Philosophical Texan

I do not know how I met the philosophical Texan, Hugh Parker. It may have been Honke who introduced us. I think it was Honke. We’d sit near a high window in this spot called The Trail Room, and the topics were Sufism, Dostoevski, Wittgenstein, Monty Python, and what Hugh called “The Floyd.” He always called them “The Floyd,” by which he meant Pink Floyd. We were crazy diamonds shining on. We were trading heroes for ghosts. The frame was Notes from Underground. Hugh was the underground man. “I am a sick man, I am a spiteful man,” he used to tell me, though he looked and sounded like neither. To me, then, it seemed like wanting to be more fucked up than you were. Hugh proved it later though, after I stopped knowing him. So they say.

Hugh was a transfer student from some unnamed community college where rivers converged, three rivers, and he lived alone in a bare apartment. The living room had one thing in it: a stereo against a wall, two waist high speakers. I never saw the rest of the house. I never saw his bedroom. I never used his bathroom. He smoked Dunhills from the one place in town that sold them, and he drank Ballantine’s exclusively. I drank brandy, cheap brandy, or gimlets, and I thought I was Thomas Wolfe. Later I’d think I was other people. Writers always think they are someone else at first. Then, if they are lucky, they think they are who they are. Some never get to this second stage.

There was something Hugh always wanted to do with me, an experience he believed I should have, and it was important to him. He wanted me to hear, as if I’d never heard it before, “Comfortably Numb.” I knew the song. He wanted me to know it more. He wanted the erotics of perception. Immersion. Your face in the speakers.

A lot of planning went into the evening. We used to get handfuls of cheap weed from some insane biology prof who kept the stuff in a grocery bag under his desk. There was that, in a bowl on the floor, and beside it, the Ballantine’s. The weed was unpredictable. You never knew how much of it you needed to smoke. One moment, you’d be lucid. The next, you’d be high as fuck, words coming out of a mouth you didn’t recognize, making sounds you didn’t intend. You’d hear them, then ask yourself, “Who said that?”

(Once this old woman ran a stop light, her car charging onto the curb. Her passenger said, “You need to be more careful.” She said, “Am I driving?” It was a lot like that).

At some point we were ready, our backs against the facing wall. With religious specificity Hugh cued up the tune, its thick, abrupt beginning and rise, like it fell from a tree it then reclimbed, its second person address. It told you hello, it wasn’t sure you were home, it said to relax. All songs are about receding. You disappear into them. This was a fever dream, your hands two balloons. Hugh had it very loud, very very loud. He’d timed it out. The song would finish before any perturbed neighbor knock on the door. In my memory it was 2:45 in the morning.

We didn’t say anything. Words weren’t the point. All Hugh did was smile, beatificially. It was a smile I knew well. It was a grin. Hugh was always grinning. He seemed to know a little more about stuff you hadn’t figured out yet. It had something to do with Texas, oil, money. He used to tell me, “Welcome to the machine.” A lot of what we talked about was where you started and where the machine ended.

I got a message from Hugh’s ex-wife. They met in divinity school. That didn’t surprise me. Hugh had a lot of worship in him. Anyway, she wanted to tell me Hugh was dead. I could see she wasn’t grieving. Her Hugh was not my Hugh. Her Hugh was a lonely angry isolated drunk. My Hugh was Syd, young Syd. My Hugh is the true Hugh. I’m saying to him, nod if you can hear me.

Psychobiography: Theory & Method

If you are here for info on PSYCHOBIOGRAPHY, these are my most recent academic overviews on the subject, one written along with the sublime Stephanie Lawrence.

•”Psychobiography: Theory and Method” (American Psychologist) > Psychobiography AP

•”Psychobiography of Genius” (Handbook of Genius, edited by Dean Keith Simonton) > Schultz, Handbook of Genius

Poetry, Creativity, and How Artists Evolve

Hey all! I interviewed the brilliant Craig Morgan Teicher for Poetry Foundation. Link HERE

Male celebrity suicide and blame

I’m quoted lots in this Playboy article by Leigh Kunkel, on suicide and the inevitable ensuing blame game, usually focused on “evil females”. Link HERE

You must be logged in to post a comment.